When over 110 campaigners from 37 countries gathered at CampaignCon in November, we had a perfect opportunity to learn about how campaigning is changing around the world.

We heard about politics and populism, gender and diversity, security and closing civic space, creativity, pop culture and innovative engagement strategies that are bringing millions into social change for the first time.

Campaigns–as always–are changing and so are campaigners. Opening up campaigns and the tools needed to run them means there are more of us: new ideas, new messages, new people. It’s a difficult, often dangerous, time to advocate for equality and justice. But, as we learned from our colleagues, friends and new heroes at CampaignCon, if we can work together it’s also an exciting and hopeful time.

Here are eight ways campaigns–and campaigners–are changing.

1. Creative campaigning is engaging new audiences with art, song, dance, storytelling.

Campaigners at CampaignCon, especially those from African countries, agreed that culturally creative tactics that engage young people on their terms are helping reach new people and many who have, for years, given up on traditional political and social institutions. Kenyans shared how JIACTIVATE uses art and dance by well-known artists to tap into the experiences of young people in Kenya. Creating cultural, not just political, messaging has helped engage young people in community and political issues.

Others shared examples of how personal storytelling is engaging new people. For instance, campaigners from the India-based gender rights organisation Haiyya are creating safe spaces for women to share personal stories. This is helping helping people craft a shared understanding of the impact that negative sexual stigmas have, particularly on unmarried women’s sexual and reproductive health. The team is building a community of women with the knowledge and support to campaign for #HealthOverStigma.

A conclusion: many more people want to be engaged in campaigns than we often believe. But people don’t engage with campaigns, leaders, movements and outreach strategies that don’t reflect them.

2. Campaigners around the world need support with innovative offline engagement. Meanwhile, distributed organising strategies are advancing in the U.S. but struggling to catch up elsewhere.

Distributed campaigning and organising is increasingly effective, even standard practice, at least in the U.S. Meanwhile, campaigners at CampaignCon reflected on the need to better bridge online and offline action in many other parts of the world–and the need for more local training and local trainers.

Distributed campaigning and organising is increasingly effective, even standard practice, at least in the U.S. Meanwhile, campaigners at CampaignCon reflected on the need to better bridge online and offline action in many other parts of the world – and the need for more local training and local trainers.

U.S. campaigners from organisations like Cosecha and Rhize shared experience using volunteer leadership development programs and livestreaming to distribute not just actions and events but also build the skills needed to create and run effective actions.

In Kenya and South Africa, campaigners characterized offline engagement, particularly the ability to move people from online/text connections into offline action, as missing from their playbook. This seems, at least in part, due to the desktop internet (think email petitions and web-based organising) bypassing regions where text messaging (and, increasingly, smartphones) is the primary connector, not desktop internet.

3. Scale: don’t leave people out of your campaigning with your choice of internet or mobile channels.

Globally, more people are able to connect to mobile devices than have desktop internet access. Two key ideas surfaced in discussions about mobile campaigning at CampaignCon:

- Many campaigners (people from the global north who have long experience with internet access and infrastructure) view online campaigning through a lens of email, websites, video, petitions and databases–some or all of which aren’t evenly distributed (or even used) in large parts of the world that are mobile first (internet second). People thinking about global campaigning and training should keep in mind that their experience doesn’t necessarily match the situation in much of the world.

- Mobile access itself is unevenly distributed. Campaigns that depend on internet connected or high bandwidth smartphones are excluding millions who rely on text messaging. We wrote about how Amandla.Mobi is using USSD messaging in South Africa.

4. We have a responsibility to build collective liberation in our organisations, our work and activism, and as individuals and communities.

The impact of unequal power dynamics, structural inequalities and oppression was a theme carried through almost all CampaignCon conversations and workshops.

The starting point, one participant noted, is that “we do not come into these spaces as equals.” We need to actively acknowledge this inequality, our differences, and understand the impact of our positions in relation to power and oppression.

A takeaway: Building a world in which we (social change makers) are not reproducing systems of oppressions but building collective liberation, requires us to listen, have honest and often difficult conversations, make mistakes, learn and do better, and be vulnerable and loving with one another.

A working group was formed to look at what we need to do in practice to help campaigns, movements, social change communities and events like CampaignCon become liberating, safe spaces for all.

5. The new skills and strategies we collectively need to win bigger–to win at the scale of the giant challenges we’re facing everywhere–already exist.

The skill we need to win are all around us but the circumstances we work in are complex and constantly changing. Spaces like CampaignCon provide a way for campaigners to connect with one another.

Campaigners, activists and organisers recognise that decisions, people and systems are related. Complexity, even chaos, is diminishing the value of long-term plans.

What we heard at CampaignCon is that campaigners need to learn faster from one another, gather expertise from other fields, test more often. There’s an appetite for defining/describing a continuous learning and adaptation approach, necessary for effectiveness in complex systems.

6. Globally, the need for expertise, support and training outpaces supply.

Specifically, there’s a big the need for training, support and safe spaces in the global south that are led by people in the global south and respond to real needs faced by practitioners.

Events and sustained spaces are needed to connect practitioners, weave together sustainable networks, and share the skills, strategies and solidarity needed to be effective.

“The biggest takeaway for me is how great the need for this kind of space is, so much more frequently and geographically varied.”

– CampaignCon 2017 participant

MobLab and colleagues around the world identified a similar disconnect between support, training and the needs of campaigners in a study earlier this year.

7. It was remarkable how many people this year operate in high risk environments and closing or closed civic spaces.

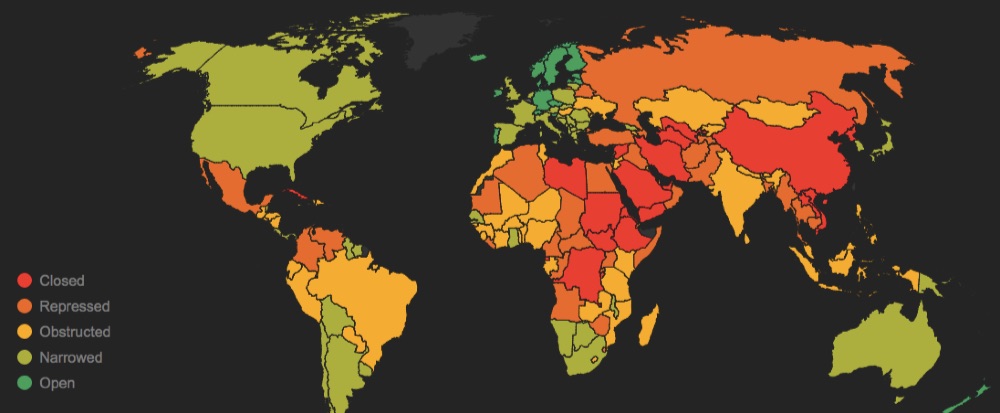

CIVICUS Monitor is an interactive world map that shares current data on the state of civil society freedoms in all countries.

People campaigning and organising for change in environments where they face state repression–from lack of a free press to imprisonment or even death – clearly stated the need for support and solidarity from organisations and individuals around the globe. Practitioners spoke of the scarcity of access to tools, tech, knowledge, skills and media amplification – as well as material resources for campaigners to keep them safe.

8. Unequal power dynamics between well-resourced global north / international NGOs and those based in the global south need to be addressed head on.

There was a stated need for more collaboration between larger, well-resourced organisations and smaller, more localised ones, but that this needs to happen with both partners on equal footing.

There was a call for international NGOs to actively challenge unequal power dynamics within their own organisations, between bigger and smaller NGOs, and crucially to help shift the current funding architecture perceived by both big and small NGOS to uphold inequalities.

Suggestions included a long-term partnership and collaboration approach to funding and working with iNGOs, but led by local activists, NGOs or movements.

As one participant put it “if you want to grow, you have to trust people.”