For being the world’s most populous and fastest growing economy, it’s astonishing how little the rest of the world seems to know about How Things Work in China. That’s just one of the reasons why I was so enthusiastic about visiting China for the first time.

China represents, in many ways, ground zero for our world’s greatest challenges — from transitioning our planet to a clean energy economy, to feeding our growing population with safe foods and sustainable agriculture, to ensuring that we can produce clothes and other necessities without the toxic chemicals that destroy communities.

For any campaigner working on these issues, China matters. So it should come as no surprise that Greenpeace East Asia is growing like crazy.

But supporting our campaigner friends and allies in China means understanding a unique campaigning landscape — where a single-party political regime forbids various forms of mass mobilisation online and offline, and where Western digital networking and communication tools are replaced by Chinese facsimiles designed to comply with government controls.

That said, if you think there’s no such thing as protests in China, you might be surprised (as I was) by the number and impact of citizen actions in China in recent years — many of which have been focused on the environmental and human health issues associated with rapid and massive development.

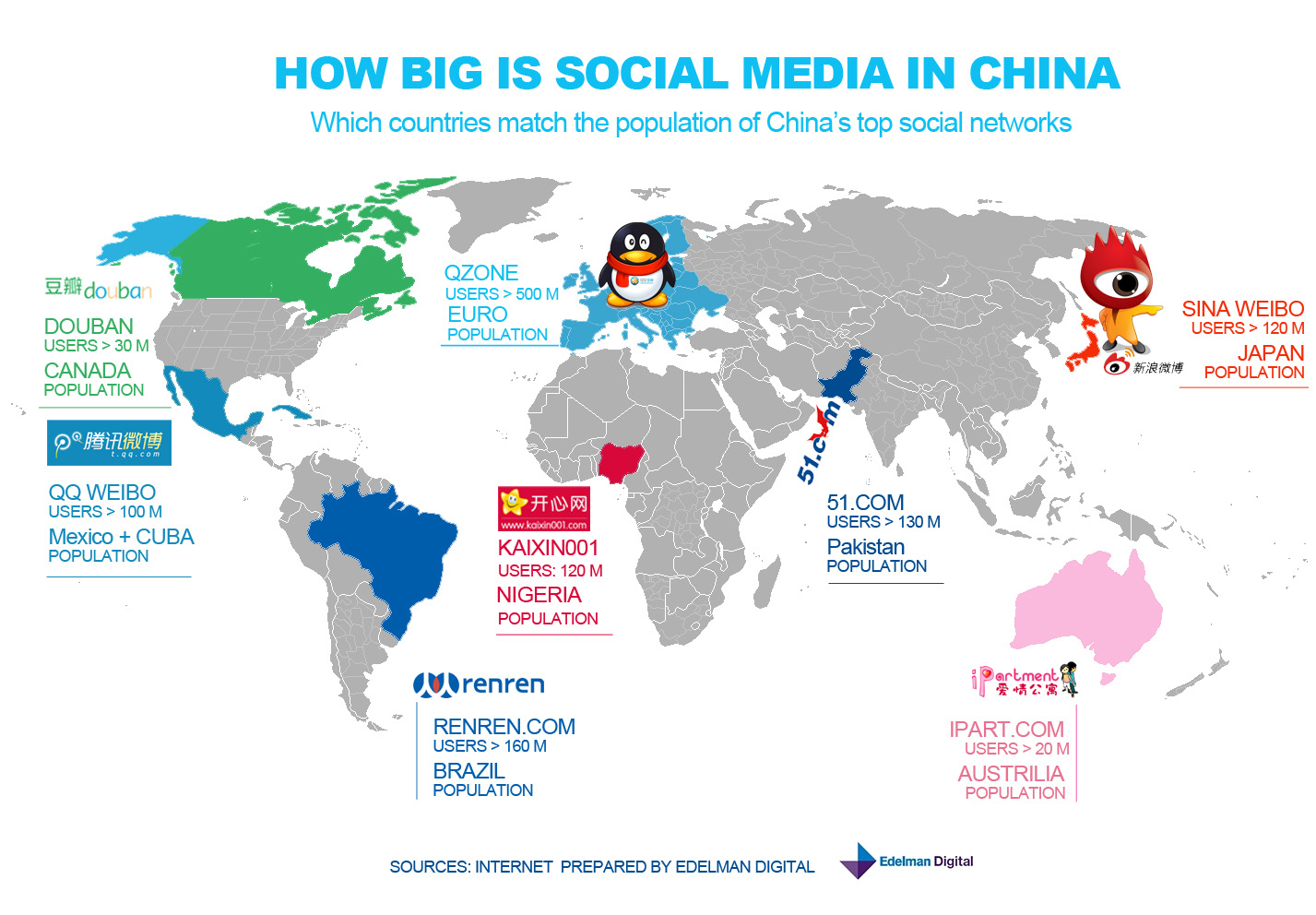

Graphic prepared by Edelman Digital China shows size of Chinese social networks compared to population of several countries.

Recently, I visited with Greenpeace East Asia staff working in mainland China and discovered a culture of organizing that works with fast-growing communities, is highly creative, and innovating rapidly — especially when it comes to using social networks.

Social Networks in China are Huge — and Different

Popular social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are blocked in China (see Great Firewall of China), but home grown, China-specific, alternatives are flourishing. Sina Weibo (or just Weibo), a Twitter-like network, has over 300 million users in China and average usage seems higher than Twitter. While Twitter counted 10 million tweets during the opening ceremonies of the 2012 Olympics, Weibo reported 119 million. Like Twitter, Weibo has been used in many community and social change campaigns. A Chinese version of Facebook called Renren currently has around 160 million users, a 30% increase over the previous year.

In a recent study of Chinese social media use, 91% of respondents reported using a social media site in the past 6 months. In the United States, that number is 67% and 30% of Japanese report using a social media site in the past six months. The authors point out that Chinese value word of mouth more than in other countries because most public information is official, state-sanctioned, and distrusted. This may further empower social network communications which are largely person to person.

Given the role of social media in helping to catalyze community action (and whole nations in the Arab Spring), we wanted to know if and how these networks are impacting campaigns in China.

Campaigning with Social Networks in China

I spoke with Shinning Shen, Senior Web Campaigner at Greenpeace East Asia, to get her thoughts on how digital media is changing the campaigning landscape. Shinning shared the story of Beijing citizens using social media to share air quality monitoring data gathered independently by the U.S. Embassy. Social networks helped put organized pressure on the government with the goal of changing air quality monitoring and cleaning up Beijing’s fouled air.

Shinning points out that social media enables more people to know about the government’s actions — and also to take action or safely apply pressure in ways that they might never conceive of doing in person:

If there is no social media then the public would never get a chance to know about the US Embassy index. Social media you can share w/ friends and spread a message. Opening a window for local citizens to be more involved and play a role in community.

There’s more on the Beijing air quality campaign below, and a recent post from Greenpeace East Asia explaining the technical aspects.

Case Study: Public pressure changes air quality monitoring in Beijing

Air quality in China, including the capital city of Beijing, is poor. That’s not news to anyone. Given how bad it is, you may not realize that the local Beijing government monitors air quality and makes that measurement public. Many have concerns about how the government goes about air quality monitoring, though. They don’t use small particulate (pm 2.5) measurements and have a one-day delay on the data. This means the public is not getting information about particulates most damaging to health and what they do get is a day old.

In May, the US Embassy set up its own air quality monitoring equipment that measured small particulates and made this data available to the public. The US Embassy numbers, because they measure small particulates, generally report air quality as being much worse than official Chinese monitors.

Not so long ago this would have gone largely unnoticed by local citizens. Social media, however, quickly spread word about the US Embassy data and provided citizens a forum for discussing the different numbers and impact on their health.

This caused a bit of a dust-up with local government officials but it helped aggregate public pressure for change. In our conversation, Shinning points out that social media created much greater awareness of the issue than would have existed without it. That was key to creating the public pressure needed to move the government to change its air quality monitoring and commit to improving air quality.