Unofficial and unreliable land ownership maps make it hard to hold a person, company or government entity responsible for environmental abuse. In 2015, fires across Indonesia created what some called the worst single man-made climate event in human history, emitting as much CO2 as Germany does in a single year while charring 2.5 million hectares of peatlands and forests. The Kepo Hutan platform seeks to open up land data, shine a light on forest stewardship and end the annual cycle of fire, blame and inaction.

Last March, frustrated waiting for the Indonesian government to release its long-awaited One Map, Greenpeace Indonesia and allies launched Kepo Hutan, an online platform using public data to identify ownership. Kepo Hutan is accessible to all and models how governments NGOs, corporations and others can use the data available now to protect forests and help local people.

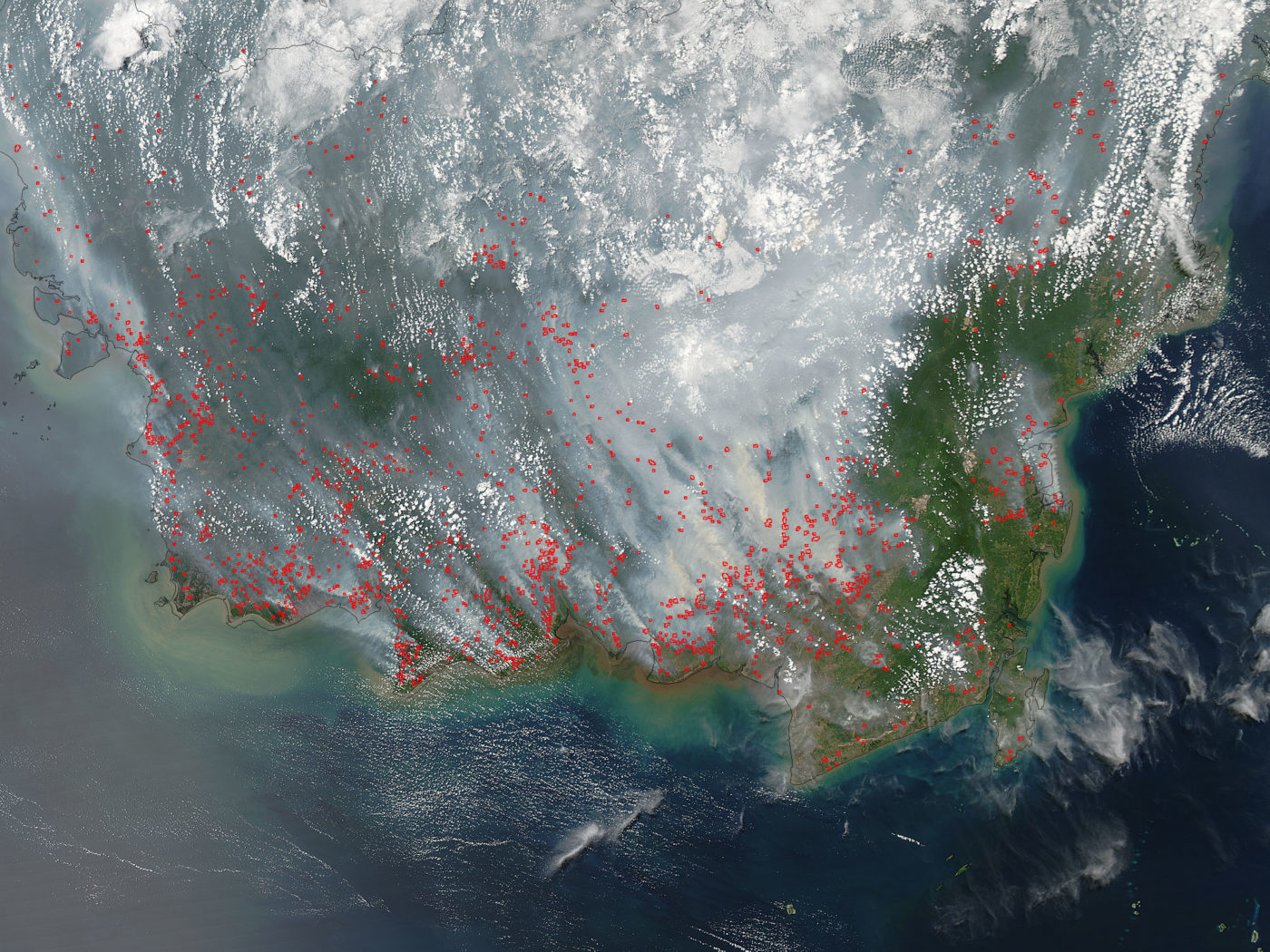

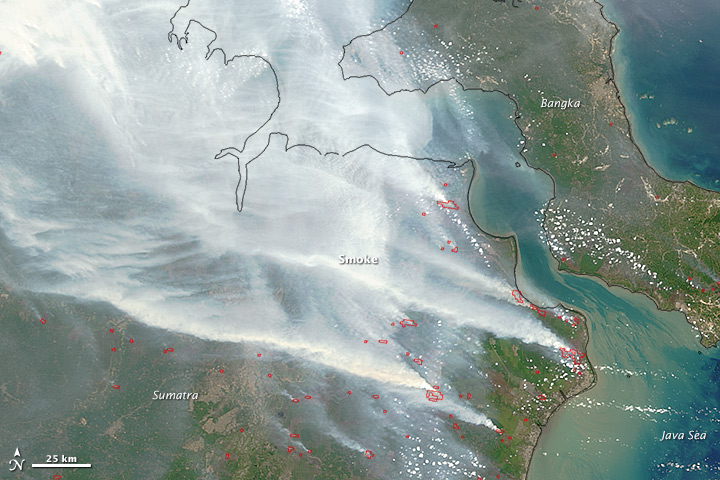

A NASA photo taken 24 September, 2015, shows smoke from fires across southern Sumatra, Indonesia.

“We are sharing the open data we received from the government [and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil]…to show the spirit of the One Map policy,” said Annisa Rahmawati, Forests Campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia. “We put this information in a place easily accessible by the public to set an example for the kind of transparency we expect from the government and companies.”

“Our goal is to involve many people in the movement to monitor deforestation and forest fires, allowing for more public participation. By doing that, it not only Greenpeace or other NGOs, but all people who can be involved.”

–Annisa Rahmawati, Forests Campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia

No One Map? Build it Yourself

Lack of information is the biggest challenge facing Greenpeace Indonesia’s work to protect the country’s vast biodiversity and tropical forests.

Few government maps are available to the public (including NGOs). Those that are fail to consider indigenous land claims or customary land uses and often show land tracts having multiple owners.

Greenpeace and its allies have been calling on the government to release a single, unified map clarifying ownership where illegal activities are occurring. In 2010, then-President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s cabinet announced that it would work on releasing One Map.

Six years after that announcement, One Map has not been released.

A map that drives campaigns

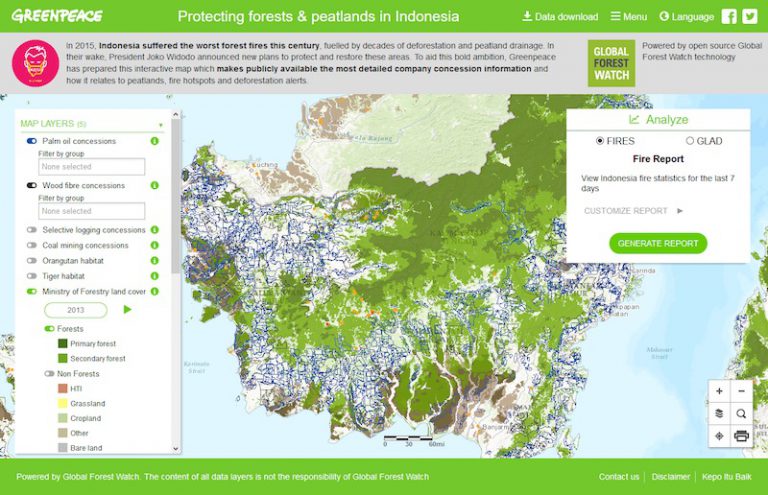

Kepo Hutan roughly translates to “Curious about forests.” It is built on the open source mapping platform Global Forest Watch (GFW) developed by the World Resources Institute.

“Kepo Hutan is great use of this open source resource,” said Octavia Payne, Communications Coordinator, for GFW. “It has always been our mission to increase transparency and access. If a company, another NGO, or an indigenous community can [better] track way their forests are being be encroached – that’s a success for us.”

“We put this information in a place easily accessible by the public to set an example for the kind of transparency we expect from the government and companies.”

–Annisa Rahmawati

Kepo Hutan is a fully web-based, Indonesian-language platform. It’s user-friendly design allows Indonesians, including those living in forested areas, to see who controls land around them and look for hotspots, fires and illegal deforestation.

“The information is transparent. Users get to see everything without having false information,” said Bagus Kusuma, Forest Campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia. “It gives power to the people.”

Transparency lifts all boats

Kepo Hutan also supports Greenpeace Indonesia’s outreach efforts. The platform provides a way to show media where fires and deforestation are taking place. Journalists use it to discover and engage with data.

In one case, a journalist from West Kalimantan used Kepo Hutan to identify a potential fire in her region. She took the information to local authorities and asked them what action they would take.

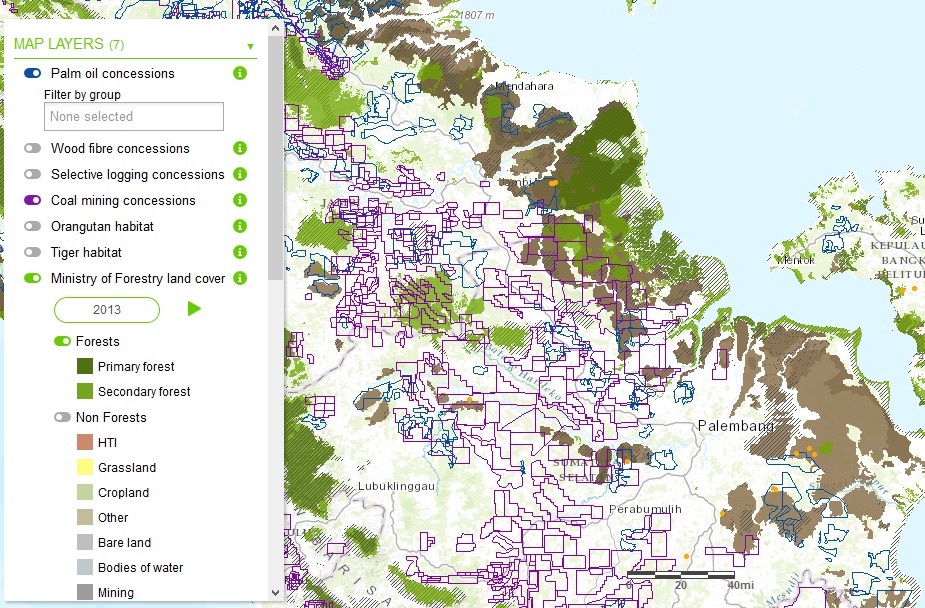

Kepo Hutan map details land ownership in southern Sumatra, the same area shown in NASA photo above.

Kepo Hutan also helps GP Indonesia engage companies. The platform can provide forest companies with useful information and breaks down barriers between them and NGOs.

“We made a webinar, inviting all the companies and talking about this mapping platform, talking about how it is useful, and how to check and make a analysis,” said Rahmawati. “We also ask them to…check if the maps we publish, the map of the concessions, are the right ones and to share maps with GFW.” This engagement has led to companies sharing more data with NGOs.

Kepo Hutan opens up knowledge about forests, and their control, to regular Indonesians. Anyone can access the information–even with a smartphone.

Land ownership and wildlife habitat data are just a few ways to build and segment maps using Kepo Hutan.

Open platforms like Kepo Hutan a model for change

Kepo Hutan is a model for what Greenpeace Indonesia and its allies want to see from the government: a single unified map integrating all concessions in a user-friendly, accessible, digital format.

“We want to show the public who is responsible for the forest fires, because as long as we don’t know who owns the land, we never get someone held responsible,” said Rahmawati.

The existence of Kepo Hutan shines a bright light on One Map’s slow, opaque, ongoing development.

“Why, after six years, doesn’t One Map exist?” said Teguh Surya, Forests Campaigner with Greenpeace Indonesia. “[We] are working for just one year, and [Kepo Hutan] exists because it is simple. The data is from the government. They just need to put in effort to manage a mapping platform.”

Making Complex Land Data More Usable

Track and see what works. World Resources Institute and Greenpeace Indonesia analyze traffic on their sites to see where users are located, the information they’re accessing and how they’re connecting. They use this data to update the site for user needs.

Engagement is key. No matter how user-friendly Kepo Hutan is, it takes time for new users to learn the tool and understand the sometimes complex data provided. Greenpeace Indonesia runw webinars, in-person sessions and even one-on-one trainings to help onboard locals, journalists and companies using Kepo Hutan.

Setting the standard for more conservation data

Data access can be a powerful tool. Activists need information to hold companies and governments accountable. That’s why Greenpeace Indonesia is embroiled in a legal battle to force the government to release high-quality forest concessions and ownership data.

“If we win, it means that civil society will get all that we need since a long time ago,” said Surya. “The data, and now also the maps.”

If they succeed, you can expect that information to be on Kepo Hutan. The ultimate goal–a One Map platform with complete government data powering it–could mean Kepo Hutan becomes redundant. And that’s okay.

“This is the kind of mapping platform that should be a standard. If the government wants to publish One Map, it should be like this,” said Rahmawati.

Data people can use. Power to build.

Kepo Hutan, and making conservation data broadly available, expands organisational engagement with local communities across the Indonesian archipelago.

“Our goal is to involve many people in the movement to monitor deforestation and forest fires, allowing for more public participation” added Rahmawati. “By doing that, it not only Greenpeace or other NGOs, but all people who can be involved.”

The broader the coalition, and the more Indonesians involved, the more likely One Map is to become a reality. That puts the power of information in more hands and means a faster resolution to the deforestation and fire crisis threatening Indonesia’s local communities and natural heritage.

Categories:

tech, tools and tactics