It’s hard to think of something more embarrassing than throwing up in front of millions of people, but that’s exactly what Sam Fuentes did at the March for Our Lives rally she helped to organise. Here’s the kicker: The Parkland school shooting survivor wasn’t embarrassed at all. Instead of running off the stage—like most of us would—she grabbed the mic and shouted, “I just threw up on international TV, and I feel great!” She went on to give an impassioned speech that shook the crowd.

Fuentes, along with Emma González, Cameron Kasky, David Hogg, and other young leaders from Marjory Stoneman High School in Parkland, Florida, stunned the world by turning their horror over the shooting deaths of 17 classmates into a mass movement against gun violence—and in record time. Most of all, they succeeded in debunking the assumption that this issue could never be wrested from the hands of powerful and well-funded gun rights forces.

Among the doubtful were older activists and professional campaigners who’d been in the organising trenches for years and had the scars to prove it. While thrilled about the success of this campaign, there was also a feeling that something was different this time. What changed? And, more important, is this the dawn of a new kind of organising and campaigning?

In short, yes. And the March for Our Lives is only one example.

Today, a new generation of activists are smashing the script and getting results. New campaigns are confounding traditional organisations that may not be able to convert themselves into nimble social movements but could learn from these upstarts.

- The Movement for Black Lives has dramatically shifted public discourse about race, especially in the wake of ongoing police shootings of unarmed black men—something that national civil rights groups have been trying to do for decades.

- The Tea Party movement‘s scrappy activist network upended a firmly entrenched Republican party accustomed to more genteel forms of civic engagement.

- The Women’s March in 2017, which galvanised millions of people, was the brainchild of activist networks—not traditional women’s organisations.

- And the architects of 350.org’s first global day of action on climate change, one of the most “widespread days of political action in history,” were a few dozen recent college grads, not well-heeled environmental organisations.

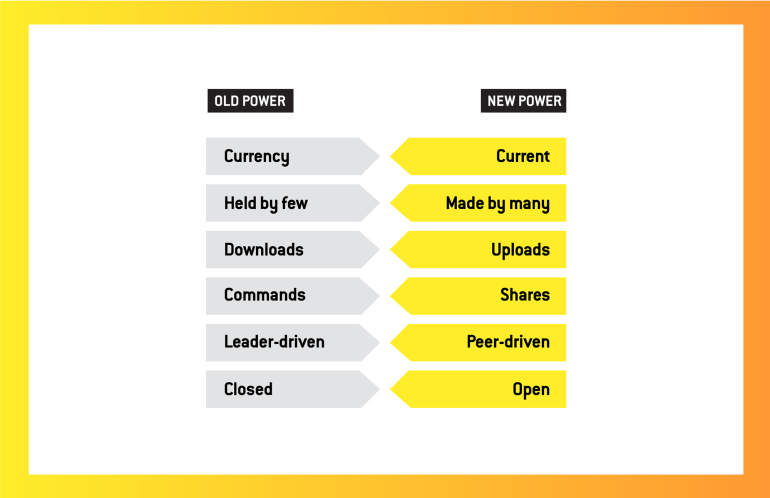

What all have in common is what Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms are calling “New Power.” These new models are organic and grow directly from the people, rather than being directed or managed by formal organisations that control what gets done and by whom. “Old power models ask of us only that we comply (pay your taxes, do your homework) or consume,” they write. “New power models demand and allow for more: that we share ideas, create new content (as on YouTube) or assets (as on Etsy), even shape a community (think of the sprawling digital movements resisting the Trump presidency).”

Technology is creating new opportunities to collectively push for fundamental changes in the rules and structures of institutions and governments. (This is not always the case for marginalised populations, however, for whom digital technology does not solve the root causes of inequality, oppression, and gaps in access to participation–and at times even exacerbates them.) New generations of young people who’ve grown up with technology embrace its participatory, collaborative, and transparent ethos and are absorbing it into virtually every part of their lives.

These changes are disrupting entire fields, from journalism to education to politics. In 2003, I got a front-row seat to this transformation as one of the leaders of presidential candidate Howard Dean’s digital organising outreach. The campaign and the movement we supported was widely credited with not only setting new records for grassroots online fundraising but also catapulting a little-known governor to the top of the polls as the presumed forerunner. Today, these approaches are changing the way social change happens.

This concept isn’t new, but it’s essential to 21st century social change efforts. Technologists like Clay Shirky, Beth Kanter, Micah Sifry, and Howard Rheingold have extolled the power and possibility of digital collaboration and participation to scale advocacy for more than a decade. Essentially, technology is less a tool or tactic and more a driver for a set of values such as transparency, crowdsourcing, and collaboration that have led to the democratisation (and in some cases, the demise) of what were once closed institutions or campaigns.

The proof of this new “people power” is all around us. New tools like email, text messaging, YouTube and Snapchat have given people the ability to challenge systems and power in ways that were previously only possible through experts and professional change-making institutions—not to mention months (and often years) of planning, organising, and fundraising. Today we can connect, communicate, raise funds, and engage in collective action at speeds and scales that were previously unimaginable.

But before we write the obits for legacy institutions, let’s remember that just because something is new doesn’t mean it can—or should—replace what came before it. When technology allowed anyone armed with a mobile phone and a Twitter handle the chance to break news, “citizen journalists” didn’t supplant the professionals. When Wikipedia become a key educational resource, educators still needed teaching degrees and experience.

What all of this tells us is that we need both kinds of power—old and new—and approaches that reflect a hybrid in order to win. Today, successful social change organisations are embracing—not running from—the kinds of technologically-driven tactics being used by the Parkland students and Black Lives Matter advocates. And new movements are working with more established organisations to capitalise on their wide-reaching networks and ability to sustain activity between and beyond surge moments.

What they have in common is a willingness to learn, test, and adapt as quickly as the culture changes. There are four specific ways in which social change organisations are adapting.

1. Beating heart: Ditch the script

Seasoned campaigners have long understood that the most effective messengers and organisers are those with the most at stake (or, like the Parkland students, little to lose). Those most directly affected by an issues can speak from the heart while many campaigners and advocates sound scripted when they cite statistics or the latest study to make their points. The result: People’s eyes glaze over. In contrast, hearing about real people’s real world experiences injects authenticity and trust into a public conversation sorely lacking both.

When Parkland senior Emma González went silent for four minutes and 26 seconds, she captured our attention by not only speaking from the heart but by making us experience—rather than “telling” us—something. She went so far off script of what’s expected at these national events that the stage manager asked if she needed help. González just kept on staring out into the crowd and then closed by informing everyone that her entire stint at the podium was six minutes and 20 seconds—the same length of time she and her classmates endured a shooter.

Former CNN bureau chief Frank Sesno, now chair of George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs, explains that good stories have three critical elements: (1) compelling characters who (2) overcome obstacles to (3) achieve a worthy outcome. Those are exactly the same elements that appear in the kinds of social change movements gaining traction such as #NeverAgain, Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo, all of which are led by survivors or people who’ve had personal experience with an issue and powerful stories to share.

We could all take a page from the first female President of Iceland. Vigdis Finnbogadottir was polling at one percent just 45 days before the election. Then, she says, “I stopped listening to all the people who told me I should do this or that to be presidential, and I started listening to my own inner voice and really found the fire in the belly that made me make that decision. And I ran the campaign in line with who I am and what my principles and values are.”

2. Step back so others can step up

We all want to be recognised for the work we’re doing, and it’s a natural tendency to want to be in the spotlight, especially when it comes to issues we’re passionate about. That desire to be front and center can sometimes hurt, rather than advance, a movement or mission.

At the March for Our Lives in Washington, for example, I saw Representative Gabby Giffords, a nationally-recognised gun violence survivor, standing in the crowd instead of onstage where politicians and organisational leaders usually are. She had stepped back so students’ voices could be heard. At the same time, she stepped up in other ways such as paying for many students’ travel to Washington.

Our colleagues at Greenpeace USA assumed a similar “unbranded” and behind-the-scenes role when they quietly setup a Movement Support Hubto contribute resources and training in peaceful protest to environmental justice groups across the country.

Sharing power isn’t easy, but social change organisations that cling to hierarchy and staff-led campaigning are likely to wither when millions of people are embracing new leadership models that emphasise collaboration, transparency, and co-creation. Moreover, new people–young and old alike–are coming to the table with new ideas and the energy to implement them.

Many still refer to the Dean campaign, for example, as one of the most innovative and effective grassroots mobilisation efforts in political history. One key reason: those of us working for the campaign were new to politics and full of fresh ideas because we weren’t steeped in the old ways of doing things, many of which just wouldn’t fly in the digital age. But even more notable was that the veteran campaigners at the helm were willing to step back and allow an entrepreneurial culture to flourish not only internally but across a national network of grassroots activists.

The bottom line: Transformative social change is going to come from organisations that place a high value on the many skills and contributions that all people—including young people—bring to their missions. These organisations see people as change agents, not just cheerleaders or foot soldiers carrying out plans designed by those “in charge.”

3. Fast feet

When Fox News host and NRA sympathiser Laura Ingraham attacked Parkland student organiser and survivor David Hogg for not being accepted into college, Hogg didn’t spend the next few days convening senior staff meetings or waiting for an interdepartmental memo outlining how to respond.

Instead, he used the public outrage that ensued to turn a personal attack into a mobilising opportunity. Hogg posted a list of Ingraham’s advertisers on Twitter and asked his Twitter followers to let those companies know how they felt. In just a few days, more than a dozen of Ingraham’s advertisers dropped her show.

The most effective social change organisations understand that as technology moves everything to warp speed, the ability to respond rapidly and nimbly matters more than ever before. That means weeding out bureaucracy that gets in the way such as ten-person-deep sign-off procedures or bloated communications channels. Yes, getting feedback about internal messaging can be great for generating ideas, but it rarely facilitates the kind of quick decision making needed by responsive campaigning.

That’s easier said than done if your organisation is more complex than a few students on a group chat. But some large established social change organisations have broken through their own bureaucracy and procedure to move at the speed of the internet.

Anastasia Khoo, former Chief Marketing Officer at the Human Rights Campaign—the largest LGBTQ advocacy organisation in the U.S.—experienced regular “fire drills” that enabled her communications and digital engagement staff to consistently improve their response. By jumping on a moment or opportunity as it unfolded, her team learned by doing. They set up, for instance, an “on call” schedule to ensure staffing when something happens in the middle of the night and developed a lean process that could produce a tweet or email out to supporters in two hours versus eight.

The benefits of moving quickly, however, typically come with a cost in terms of quality. This naturally makes brand conscious organisations nervous. The MSD students, for example, used a relatively lean and rough design process—which took less than an hour—to develop the viral “Enough Is Enough” meme that countered an NRA post asserting the right to “control my own guns, thank you.”

These students are part of a generation of digital content creators who are comfortable with blending humor, social values, and creative media into timely memes that travel far and wide. It’s a different language than what most campaigning and advocacy organisations grew up speaking. But one thing hasn’t changed at all: agreeing an overarching vision and message provides team member with the autonomy needed to respond quickly and creatively when opportunities arise.

Fluency with these newer digital media, communications, and engagement tactics requires both willingness to embrace risk and new skill-sets, and the most successful organisations are adapting. This may be why we’re seeing a boom in job descriptions at social change organisations for roles that could easily be mistaken for postings at digital newsrooms like BuzzFeed or viral media sites like Upworthy.

4. Dream big to go big

Elon Musk has an audacious plan to populate Mars, and we’ve all heard about it.

While it may be counterintuitive, I’ve found it’s often easier to go big than small. If it’s not a big bold idea, people ask, how are you going to mobilise interest and excitement? After all, which politicians and leaders build support fastest? Those with a vision of the future you can taste, touch, and feel — not data sets and six point plans.

Behavioral researcher and author Simon Sinek uses Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous speech to explain this key element of movement building and social change in one of the most viewed TED talks of all time. “He gave the “I Have A Dream” speech, not the I have a plan speech.”

Sinek points out that King spoke about the future positively and so vividly we could imagine it with him. “He spoke for a different world, how to go from here to there. And he so beautifully described what there is.”

Big visions mobilise big action because if your vision is inspiring enough, people will see how the path to victory requires them and countless others stepping up. King’s vision mobilised a quarter of a million people to make the trek to Washington DC (long before the internet) and the MSD students inspired over a million to stand up against gun violence in DC and cities across the country.

Approximately 5 million people worldwide took action on 21 January 2017, as part of the Women’s March. Some of the million participants in Washington, DC, are shown here in this public domain photo. Organising for the march began on 9 November 2016, when one woman in Hawaii created a Facebook event.

Today’s most effective organisations are developing big visions and open campaigns that depend upon “new power” and simply can’t be won with staff alone. “The future will be a battle over mobilisation,” Heimans and Timms write in New Power. “The everyday people, leaders, and organisations who flourish will be those best able to channel the participatory energy of those around them.”

These organisations flourish by creating clear roles for many people to help scale campaigns and achieve big wins (or “many hands” as we like to say in our Anatomy of People Powered Campaigns). There are a growing number of organisations embracing this principle to engage volunteers in meaningful work that gets greater results, and we highlight several of them in this toolkit we developed with Capulet: Beyond the First Click.

The March for our Lives was pretty big, but it got even bigger when other students emerged, calling on fellow students across the country to join a nationwide school walkout on April 20 (anniversary of the Columbine massacre) that would keep pressure on politicians and continue building local power. It’s a great example of the type of emergent, distributed leadership that we can only hope to see when campaigns are designed openly, with big, clear visions that reply upon mass participation.

From deficit to abundance: Adopting a movement mindset

Could your organisation pull off a national march in five weeks? Without any infrastructure or paid staff? With little financial support? And while leaders are still reeling from major trauma?

A lot of people told the Parkland kids that what they were attempting was impossible. Luckily, they were able to ignore these concerns because they weren’t fixating on what they didn’t have. Instead, they had a “movement mindset” that allowed them to focus on creatively and efficiently using the resources they did have.

Organisations of all sizes are discovering that they can take a page from social movements and find ways to act before everything’s in place or completely figured out. Through participatory planning, rapid audience testing, and real-time ongoing improvements, organisations are developing initiatives that can be successful in rapidly shifting and unpredictable contexts. In short, the perfect is no longer the enemy of the good.

Will our most vital nonprofit advocacy and campaigning organisations reinvent themselves to be fit-for-purpose in today’s world? I’m optimistic.

During the last few years, my colleagues at the Mobilisation Lab have seen massive organisations like Greenpeace, Amnesty, and Save the Children integrate fresh approaches into their work. We’ve helped campaign teams inside these organisations host “Campaign Accelerator” planning workshops that blend human-centered design methods with “lean” principles and other advocacy strategies aimed at building more innovative, people-powered campaigns in a fraction of the time that typical bureaucratic planning processes would take. The result: Nimble, quick, and smart organisations able to respond to rapidly changing circumstances.

Lots of organisations say they’re interested in innovating their strategies, tools, and tactics. But the ones that actually do — and in turn become more effective — seem to have two things: leadership willing to embrace the four principles above and a critical mass of internal changemakers fearlessly asking if the status quo is truly going to take their organisation where they need to go to achieve real impact.

Top photo: On 24 March 2018, in DC and other cities, hundreds of thousands of students and others marched to demand common sense gun control in the wake of deadly school shootings in the US. Photo by Flickr user Mobilus In Mobili. CC BY-SA 2.0.