One early morning in December 2012, Tianjie Ma stood beside a gigantic discharge pipe, watching as it spit dirty water into China’s Qiantang River. Behind him, Greenpeace activists worked on a video and photo shoot.

They dressed 10 mannequins in designer jeans and placed them on the shoreline, facing the water. The chemicals polluting the river were the same ones used to make the jeans on the mannequins.

Webcams inside the mannequins heads would transfer live images of the act, back to a press conference in Beijing. Greenpeace calls this bearing witness.

This is Tianjie’s most memorable moment from the Detox our Fashion campaign, an initiative Greenpeace launched in July 2011 to draw attention to the link between international clothing brands and textile manufacturing facilities in places like China that discharge hazardous chemicals into the water.

A Greenpeace report called Dirty Laundry, the result of a year-long investigation, detailed the environmental impact of the clothing brands’ supply chains.

“I think that was probably the most successful Greenpeace action that we did in mainland China, and I think the response we got from the public is also very positive,” says Tianjie, Greenpeace East Asia’s Deputy Programme Director.

Greenpeace activists installed a group of mannequins around a large waste water discharge pipe belonging to the Linjiang Waste Water Treatment Plant (WWTP), in Xiaoshan District, Hangzhou. The mannequins all look out towards the gushing effluent from the pipe mouth, ‘witnessing’ the Qiantang River pollution through live webcams.

Big risk means big reward

Tianjie and the group of activists set up the mannequins over two days, always before dawn, to avoid catching the attention of local authorities.

The Xiaoshan District in Hangzhou is home to the Qiantang River and more than a third of China’s dyeing and printing activities for the fast fashion industry.

Suppliers for big global brands take advantage of communal wastewater treatment plants to conceal dirty pollution. The mannequins were bearing witness to the environmental crime, although it was a risky and complicated task.

Risks are necessary with this kind of action, Tianjie says.

The risks paid off.

One volunteer who helped with the action later wrote a piece on Weibo — China’s Twitter-like social media platform — that attracted more than 13,000 forwards within a couple of days.

The fact that bearing witness, a Greenpeace value, resonates within Chinese society is powerful because it penetrates cultural boundaries and the online community of the Chinese public, says Tianjie.

Beyond coverage of the action involving the mannequins, a campaign video in China received 8.2 million page views in 11 hours before being censored. A Detox fashion anime video was on a list of viral videos the week it came out, and the latest Detox campaign video has over one million views on YouTube, after getting great promotion from sites such as Upworthy.

Go big or go home: Detox targets big brands Nike and Adidas

When the campaign began, the Detox team chose Nike and Adidas as their first big brand targets.

The team launched an online petition and released a video showing people competing against one another wearing the brand apparel with the Detox logo.

Within two months, Puma, Nike and Adidas all committed to publicly accept the Detox challenge: to phase out hazardous chemicals in their supply chains by 2020.

The campaign shifted its target to high-street fashion from sports apparel. So far, 20 major clothing companies have publicly committed to “Detox” their supply chains.

These international brands — which range from luxury labels like Burberry and Valentino to high-street giants such as Zara, H&M and Levi’s — are creating elimination plans for most hazardous substances and providing more transparency around the chemicals their suppliers release into waterways.

The campaign has mobilised millions of people around the world, making the brands accountable to those who hold the most power for their success: the consumers, who are the people who love and wear their clothing.

Answering the question: Why should I care?

Tianjie has been part of the Detox campaign since its conception. He recalls early discussions amongst the campaign team about the need to push the issue of toxic pollution higher up the political agenda.

The campaign team brought forward the idea of achieving this goal through a symbolic industry that everyone relates to — the textile industry — and its heavy use of chemicals and water.

Zeroing in on the textile industry, which people interact with every time they buy and wear clothing, helped make the pollution more relevant to people not directly affected by polluted waters, notes Zeina Alhajj, Head of the Detox campaign.

Another early hurdle was simplifying the issue. Because most people associate the word toxic with something bad, the team was able to build on that assumption to take people on a journey of the correlation between what they buy and wear day to day, says Zeina.

The Detox campaign takes an audience-centric approach, which is embedded into everything the campaign does, and starts with its name. Rather than calling it something like the “Toxic Water” Campaign, Detox is much more action-orientated and solution-focused (the campaign aims to literally “Detox” the world from hazardous chemicals) a fact that many of the influencers the campaign has managed to engage have cited as something that drew them in, says the campaign’s Creative Director, Tommy Crawford.

What Could Be Improved

More savviness in China’s social media.Tianjie says there is a gap between the ability to deliver through traditional media outlets and social media channels, noting there was a big investment in pushing the campaign through Weibo and We Chat in China but the return was not as good as expected.

Invite people into the design process. Some campaigns create space for supporters to design different elements, such as the campaign slogan. Detox has yet to do this kind of co-creation, and involving more people in the design work and messaging may be a next step, Zeina says.

Harnessing celebrity power. Several celebrities have pledged their support to the campaign, from fashion designers to models and creatives. Having more engagement and resources devoted to the celebrity work would have been well-invested, Zeina says.

The Detox logo, which has been used widely as part of the campaign — featuring on everything from t-shirts, to videos, to temporary tattoos handed out in their thousands at music festivals and shopping malls — includes the Chinese symbol for water as the “X”, helping to cement both the connection with water, and the importance of China, into all communications.

“It created something that we can have central, global identity around,” Tommy says, noting also the associations people carry with the word Detox (mostly linked to health and cleansing our bodies) and how this is a useful bridge between the personal and the global when talking about the campaign.

And because many global brands are using suppliers in China, people can relate to the issue as consumers.

“By making choices and being a conscious consumer I think the brands will get the message that they cannot just produce products while at the same time destroying our planet,” Tianjie says. “I think they have to find ways to do it in a more green and clean ways without toxics and without compromising our future generations.”

The Detox campaign isn’t focused on one particular brand, which allows it to move nimbly between targets, because there is a common goal and group of people engaged.

“I think too often we play within the frames of the status quo and talk in the adopted language of the actors we are trying to change,” says Tommy, “whereas with Detox, we reframed the issue and turned it into something more positive and aspirational, which then allowed us to engage certain audiences that helped make a massive difference on this campaign.”

Campaign team needed space to ‘fail, learn and propose new things’

Greenpeace made a strategic decision to use a motivational values approach to engage supporters called Values Based Segmentation (VBS): a model that aims to understand what makes people tick.

Making strategic decisions and giving the campaign team and the communication team “the space to experiment, to fail, to learn, amend and propose new things” were key, says Zeina.

The VBS model Greenpeace uses comes from Cultural Dynamics Strategy and Marketing in the U.K. and is made up of three main groups called Pioneers, Prospectors and Settlers.

Detox focuses on two values models: the “Now People,” who are trendy and conscious of what’s new, and the “Transcenders,” who are culture shapers.

The campaign team grappled with the challenge of communicating with and identifying the audience, concerned about not being inauthentic while still appealing to them, notes Eoin Dubsky, Community Communications Specialist at Greenpeace International. Often, when the public thinks of Greenpeace, images of banner dropping and big boats come to mind and not a hip, young brand, he adds.

“It’s a fine line and I think that we were successful enough for the brands to go, ‘Oh shit, these people who love us are now looking to Greenpeace,’ it’s not just Greenpeace supporters who are looking to Greenpeace it’s the fashion industry who are writing about this,” he says.

If the campaign team hadn’t implemented VBS, Zeina says they likely would have kept focusing on the fact that toxics are bad, rather than having people understand the campaign and get active.

“With this approach we got people to act with us, to understand the campaign and the campaign demand and by acting with us we added the pressure on the companies and forced them to make a change,” she says.

The Zara campaign had good interaction with the community from the start, with the first petition receiving more than 100,000 sign ups in less than 24 hours. This prompted Zara to call and ask for a meeting, says Zeina, noting that is an example of people power.

Do you speak the language of fashion?

Detox is different from other Greenpeace campaigns targeting brands and leveraging the power of consumers because of its sophisticated use of narrative, says Tianjie.

Detox is designed to penetrate the fashion industry by adopting its language and producing high-quality fashion shoots with professional models. Campaign material is friendly for fashion media and magazines to use.

“There has been a conscious effort to speak the language of your target,” Tianjie notes, which differs from some other campaigns that look to talk to people who already agree with Greenpeace.

“The whole feel of the campaign is very different — very young, very fashion — that’s how we would like to position it in the public’s eye,” he adds.

The fashion victim theme became a narrative for the whole campaign, playing out in in different ways, including a press conference in Beijing where professional models made to look sick walked down a catwalk.

The campaign has a consistent feel and style that managed to penetrate into a sector of the media and online community that is new for Greenpeace, says Tianjie.

Being a campaign going after the fashion industry, it was important for it to look slick, be clear, and appeal to people who are outside of Greenpeace’s usual support base, says Ana Hristova, Digital Communications Specialist at Greenpeace International.

Many campaign materials spoofed the target’s brand. For example, a Levi’s ad with water in the background was changed to look like toxic water, and the company’s “Go Forth” tagline was changed to “Go Forth and Detox.”

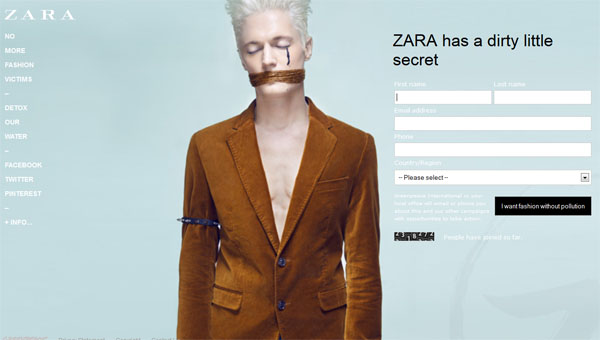

One particularly striking Detox image is from a photo shoot in China shows a model acting as a fashion victim, wearing a mask over her mouth and nose. The photo resonates as there are also air pollution issues in China. Many of Greenpeace’s Asian offices were still using this image as their Facebook profile picture months later, says Ana. The campaign used the photo during the Zara focus, which included creating a website mirroring the company’s site with the images showing models in masks.

A Detox website mirroring Zara’s shows models in masks. Zara committed to go toxic-free Nov. 29, 2012.

Stickers and striptease: How Detox used new methods to mobilise

Detox activists engaged in new and creative methods during mobilisation efforts to put pressure on brands and see results.

The Detox campaign set-up the world’s largest co-ordinated striptease outside brand stores as part of its offline mobilisation efforts. It was a central concept that locals adapted to fit the cultural context: In the Netherlands, several people got completely naked outside a Nike store, whereas in the Philippines activists removed clothing to show more clothing bearing Detox messages.

In November 2012, activists organized a mannequin revolt in 80 cities across the globe. The storyline was that Zara’s mannequins were sick of wearing hazardous-chemical filled clothes every day and were quitting their jobs to join the Detox campaign.

Again, activists made creative adaptations to the idea in various cities. In Thailand, mime artists were dressed as mannequins doing the walkout, and in Mexico City, people dressed as mannequins did Thriller-esque dances outside the store.

The use of Detox store stickers was a new move for Greenpeace, a break from the banners that people often see during protests, notes Eoin. During Days of Action, where people around the world mobilised to send a message to a particular brand, volunteers plastered the stickers, featuring the Detox logo with different taglines, on store windows.

Staff members working at the clothing stores thought the stickers were something the brand was leading, not realizing that it was a campaign attack.

People whipped off their clothes in Bangkok to join more than 600 people worldwide to strip outside Adidas and Nike stores.

Celebrity engagement heightened the campaign with fashion designers, models and creatives signing the Detox Manifesto, a call for toxic-free fashion with a story people could be proud to wear.

Harnessing the power of people

Since Day 1, Detox team members are working to make Detox be an inclusive, people-powered campaign. Greenpeace has a mentor role instead of being front and center, keeping the focus on the supporters.

Keeping the focus on the individuals involved is powerful because it helps reinforce “a story that benefits every other campaign that we work on, and that is that people acting together make a difference,” says Tommy.

“It also encourages people to get more involved, and helps people see the value of their actions as they add together or inspire actions from others,” he says.

The role supporters played in convincing each brand to Detox is different, says Senior Campaigner Ilze Smit, but for some — like Zara — people power clearly made a big difference.

Yet, while Global Day of Actions were very important to the campaign, they are not necessarily truly people powered, notes Ilze.

“People power is when you leave it really to the people to make the campaign, and the Global Days of Action are often highly coordinated by Greenpeace,” she says.

Greenpeace has big ideas on improving people power, she says, noting in the past the organization has learned to let go and let people do things.

Guerrilla labelling sharing the hazards in a Levi’s store in Hannover.

When G-Star was being targeted, Greenpeace Netherlands for the first time asked its Detox campaign supporters to leave a message on the company’s Facebook wall. Ilze, who was leading the effort, says the reaction was “overwhelming.” Supporters were sharing the message about how they like the brand but don’t want to be wearing toxic jeans, without much direction from Greenpeace.

Ilze says it is a good example of how people power works in reality.

“We have to trust our supporters. They are bringing forth the right message and that will make a difference for brands because they listen to their consumers,” she says.

For other brands, people power isn’t having the same effect. Gap, for example, which has been caught “sponsoring” toxic water pollution scandals in China, Mexico and now Indonesia, has yet to make a commitment to Detox.

“People power is very difficult to measure, it’s very difficult to assess,” says Zeina, noting there are many ways people have engaged in the campaign, from the petition to following on Twitter.

A campaign video released in October 2013 on how people power is cleaning up fashion is the best example of people power in the campaign, says Zeina.

Because Greenpeace’s focus was releasing the Arctic 30 activists who were held in Russian jail, the organization didn’t have the potential to push the video out using its internal lists or social media accounts. But the video managed to go viral, with more than 750,000 views in one month, without the organization pushing it.

“(The people) did the dissemination, talking about it, spreading it around their network and taking it forward. And for me this is a concrete example of the power of people power because we really didn’t have to do it ourselves, we were bound by international reality of the organization,” Zeina says, noting the content is very information rich and not the type they expected to go viral.

Making high-pressure decisions in the moment

Key Successes

Reaching new audiences: Greenpeace was asked to bring insight into creating an eco-fashion dress worn by Naomi Harris at the 2013 Academy Awards, and is receiving requests to speak at different venues including creative strategy events and eco-fashion interviews.

The campaign’s focus on creating slick, fashionable materials seems to have workedgiven its coverage in the style and fashion sections of traditional media, and lengthy pieces in Fashion and Lifestyle outlets , which helped bring the issue to the attention of important change-makers.

The Detox team developed an online mobilisation tool to combine tweets from supporters on Twitter and China’s Weibo, bringing previously separated voices together and demonstrating the campaign’s broad reach.

By the numbers: 20 major clothing companies have committed (as of February, 2014), tens of thousands of media articles have covered the campaign, millions of people have taken action, and Tens of millions of people have been reached.

Having the organization aligned gave a huge amount of power for people to work together and put maximum pressure on the brand. It also led to nimble decisions, says Tommy.

There was a direct line within the corporate dialogue team, and information could be sent back and forth to the project team to alter strategies and tactics quickly based on how things were progressing.

“We could decide to escalate or de-escalate certain activities depending on feedback from the brands,” says Tommy.

With such a dynamic campaign and with so many companies involved, having an empowered core-team enabled members to produce materials and distribute them quickly to Greenpeace’s national and regional offices.

In-house production made it easier to do last-minute modifications and changes to content, images and websites.

Colleagues in other Greenpeace offices have expressed a desire to customize their own webpages because content that works in one region may not in another. Ana and Eoin coded the Detox landing pages, making it easy for them to support changes for other offices, or the offices could customize the pages themselves.

Compared to other campaigns Detox has been very dynamic with a lot of output, says Ana. Each target required completely new materials for the brand, which was challenging on such short timeframes.

The Detox isn’t over

The Detox strategy is evolving.

Some of the items the campaign team created have yet to be released. In addition to more targets, the campaign will also focus on following the implementation of commitments from the companies.

“What we’ve asked from them is revolutionary, and they are doing the right thing,” says Eoin, noting the brands that have committed deserve a pat on the back and some positive public relations.

“What’s exciting is that the implementation of their commitments — which is already taking place — has some broad-ranging halo effect beyond the reduction of toxic chemicals,” says Tommy.

The momentum created can also be harnessed to push for more ambitious toxic elimination targets both within Chinese policy making and other industries, notes Tianjie.

But one challenge is expanding the audience without losing the ground that has been gained, says Zeina.

“Our key objective in the campaign is to resolve pollution issue, is to get government as well as company to protect our water resources,” she says. “Combining various audiences and working with various audiences in one campaign I think is the next challenge that we are going to have to deal with.”

Campaigning is about learning, developing, executing and the most important aspect is to have fun, says Zeina, noting the campaign team is having fun and so are the activists.

“It’s their win as much as it’s our win and for me winning always brings a smile to anybody’s face,” she says.

“Every person that looked at our website, every person that pressed a key to support the petition or send the video to their friend, is part of that win. I honestly believe that, and that to me is the power of mobilisation and engagement, we are all partners in that positive crime I would say.”

What Greenpeace learned

Everyone is a media consumer and creator. Today’s participatory media environment plays a key role in defining modern brands and how they are perceived. Campaigns like Detox are designed for this networked age, where activists can easily access a campaign, voice their support or concerns, and scale a campaign in a highly public context — more rapidly than ever before. Knowing how quickly networked individuals and organizations can redefine a brand’s image, several companies preemptively committed to Detox before becoming a target — a more rapid reaction than would have likely occurred in previous eras.

Do research — then do some more. Eoin says “you could fill many desks full up to the ceiling of desk research that was done,” making it a well-researched project long before the first call went out to a target company.

Be flexible when it comes to targets. The campaign team planned what companies they would target and in what order, but they learned to be flexible as targets started committing to Detox in a different order than expected.

Line up small, achievable, winnable steps. When the sports brands committed there was a feeling of, “Wow, I just did a little campaigning and succeeded,” motivating people to stay involved and keeping journalists interested as they followed the unfolding campaign story.

Align your entire organization for the biggest impact. The Detox campaign has had several big push periods to date, where all of Greenpeace is aligned and focused in the same direction. Being present in 28 countries, with 30 million followers and supporters, means focused pushes can lead to powerful results and momentum.

Streamline production of materials. The campaign team learned how to produce a lot of creative products with clear accountabilities for pushing them out.

Categories:

tech, tools and tactics