Recent attention focused on cutting edge distributed organizing tactics deployed in the Bernie Sanders U.S. presidential campaign will surely trigger a sense of déjà vu for those tracking the field since Obama’s campaign in 2008 and for digital veterans who recall Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign.

Each race produced memorable campaigning breakthroughs and left behind a toolkit that organizers in other movements have adapted and repurposed toward advocacy and activism.

Political campaigns as incubators for new mobilisation strategies

There is clearly a special set of circumstances that emerges every few years and with certain candidates that turns political races in the U.S. into quantum leap moments for digital and people-powered mobilisation strategy. To find out what makes certain political campaigns such drivers of innovation, Mobilisation Lab spoke with some key observers who share a long view of political campaigning practices.

For Micah Sifry, Executive Director of Civic Hall, U.S. campaigns are particularly potent digital mobilisation labs. American elections bring together budgets rarely seen by organizers elsewhere and, relative to other campaigns around the world, last a long time, providing the timeline needed for extensive testing and optimisation.

Not all U.S. campaigns are alike when it comes to cutting edge strategy, however. Underdog status, Sifry says, provides certain progressive candidates a fertile base for innovation. “Typically, underdogs are forced to experiment where the front runners or the establishment candidates do less experimentation,” he observes. Sifry points out that Howard Dean in 2004 and Obama in 2008 fit the underdog bill and ran innovative campaigns. Obama, a front-runner in 2012, ran a more conservative reelection campaign.

The strategic legacies of the 2004 Dean and 2008 Obama campaigns

The Dean 2004 and Obama 2008 campaigns both assembled savvy teams of young operatives. Each tried and tested new digital strategies at massive scale according to David Karpf, professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University. Once the races were run, advocacy groups and nonprofits benefited to some extent from the experience of the campaigners involved. Organisations were also able to use proven (or simply tested) the campaign’s mobilisation tools and tactics.

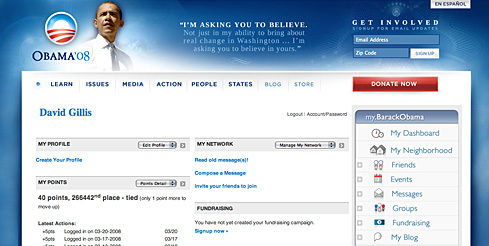

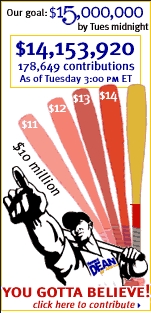

For Karpf, the Dean campaign and its pioneering use of Internet sites such as Meetup for political organizing created a “big bang moment that convinced many people that mass participation in all kinds of political activity was possible on a scale they hadn’t imagined possible before.” This became especially clear through Dean’s small donor online fundraising, he observes, which successfully raised millions and later inspired groups like Avaaz.org and Sumofus to do the same to fund their activities. As for Obama’s first campaign in 2008, Karpf believes it built the same kind of grassroots supporter energy that the Dean campaign had raised through its Meetups only this time, established a central framework that “channeled this energy towards specific end goals like door knocks.”

The Bernie Sanders campaign: A massive distributed organizing lab

Can you make Sanders-style “Big Organizing” happen in your cause campaign? 3 questions to ask before you try.

Can I rally support the same way?

A well-loved candidate can count on the active energy and support of thousands. Does my cause motivate supporters to pledge their time and effort in a similar way?

Am I driving simple actions?

Political campaigning often drives collaboration around very simple tasks such as phone banking and door to door canvassing. If you are not driving grassroots supporters towards simple actions, political mobilization tactics may not work.

Can I sustain it over time?

Political campaign tactics only need to run for a few months while other issues require years of sustained pressure. Make sure that the strategy you’re considering can work with a longer timeframe.

Cutting to the present, the Sanders campaign has been singled out by pundits for its digital prowess and savvy use of social media. The most impressive breakthrough for campaigners, however, will surely be the Sanders camp’s massive distributed organizing system. Set up by key organizers Zach Exley and Becky Bond, this system was recently explored in interviews by Micah Sifry. Dubbed “Big Organizing”, this campaigning approach encourages Sanders’ volunteers to start and lead local rallies and has so far generated over 60,000 events across the U.S. Big Organizing has also handed control of canvassing tasks such as phone banking directly over to its grassroots base. With this volunteer support, Sifry notes that the Sanders campaign with its 800 paid staffers has been able to achieve the same call volume as the Obama campaign, which had over 4000 on its payroll.

The Sanders campaign’s massive distributed system has also come up with its share of clever hacks for turning online engagement into real world action. In a brilliant combination of low and high tech, organizers would use targeted social media outreach to get supporters to attend local rallies and then, once on site, would get these attendees to sign paper commitment sheets for tasks such as phone banking. Using their smartphones, organizers would then use snap photos of these pledges and use them to build an online follow up database that would put those commitments to work.

For David Karpf, there is no doubt that the Sanders campaign will inspire a good number of organizations to try build their own distributed campaigning models. “Before Bernie, people didn’t really believe that you could scale distributed organizing effectively. You can now expect to see new startups that will package the tools used in the Bernie campaign for other groups,” he predicts.

Looking further afield, recent campaign practices within the U.K. Labour Party campaign reveal that tactical innovation is not restricted to the U.S. alone. A key campaigner involved in Jeremy Corbyn’s successful leadership run has described a ground game for Mobilisation Lab that resembles Sanders’ in terms of its empowerment of volunteers to run many tasks formerly entrusted only to staffers. To help supporters gain greater autonomy, the Corbyn team even designed a canvassing app that allowed their distributed teams to set up phone banks from wherever they were organizing across the country.

Knowing what to pick up and what to leave behind

While the political campaigns described above are certainly breaking ground and coming up with interesting tools and tactics, campaigners outside the political realm should take a moment to evaluate whether or not they can adapt these innovations to their own work and contexts. Here, David Karpf has a warning to those who would make easy parallels between cause-based advocacy and political campaigning. Unlike social issues, he observes that “Elections are conceptually really simple as they have an end date and a clear definition of victory.” In addition, he notes that the money, mass participation and staff available to political campaigns often provide a scale that is hard to match outside the world of presidential races. These unique factors mean that some things that work well in the elections universe may not run the same way under different conditions elsewhere.

While not everything crosses over from politics to the work of campaigning for social change, there is no denying that political races give certain strategies a major boost and drum up a lot of excitement and discussion in the process. If anything, the high profile validation that mobilisation strategies enjoy during major elections often give advocacy campaign innovators a leg up when trying to sell through these innovative approaches even years after the races have been run.

Categories:

organising, mobilising and engagement