Taiwan has in recent years experienced some of the world’s most dramatic protests. The Sunflower Movement, a youth-driven but cross-sectoral coalition famously occupied the Taiwanese Parliament for more than three weeks as it fought against a controversial trade deal that they felt would impinge on Taiwanese sovereignty.

Software, social media and other rapidly evolving technologies are fueling a digital democracy and political change in Taiwan. Connected networks support mobilisation leading to greater government transparency.

Neutral Tech, Mass Movements

The Taiwanese public and international audiences used “traditional” social media platforms (e.g. Facebook, Line, Twitter) for communication. Meanwhile, organizers and activists relied on an innovative digital communications and collaboration system powered by several open source tools including Hackfoldr and Loomio.

Tools could be quickly adapted to specific needs, collaboratively managed, and responsive to changing needs and demands. Ultimately, this platform opened the campaign to broader participation and helped influence how the Taiwanese government engages citizens.

“There was already this community of people interested in using tech to improve citizen democracy and because that was already in place, the movement was resourced with techniques and technology for organizing really effectively,” said Ben Knight of Loomio.

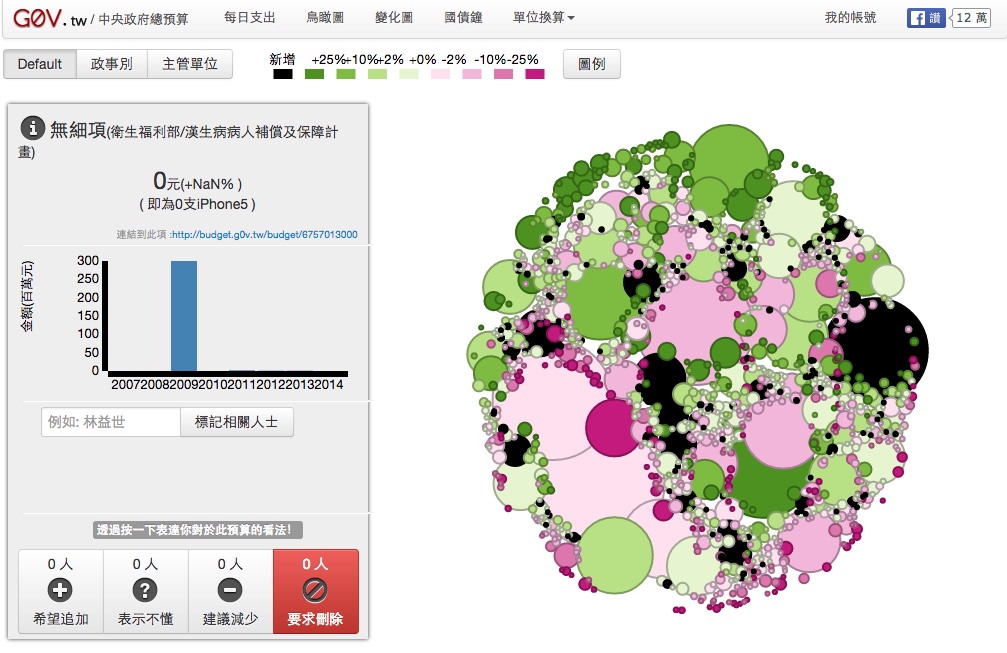

Taiwan has been at the forefront of digital democratization for some time. In 2012, Taiwanese netizens created alternative, crowdsourced .g0v (a number 0 where an O would otherwise be) versions of Government websites where they released data in formats that helped people more easily understand what government ministries were doing.

“Most of the technologies we have deployed in Taiwan were neutral; they were intended to encourage people to talk, that’s all. We had a very strong code of neutrality,” said Audrey Tang, a self-professed “conservative anarchist,” and member of g0v.tw, now a civic movement aiming for true, participatory self-government.

Youth leaders, g0v.tw, and other hacktivists all came together last year when the Government’s move to limit public debate on a trade deal with China angered citizens upset at the blatant disregard for democracy and potentially adverse economic impacts. In just a few days, this morphed into a mass movement.

Technology played a key role from the very beginning. During the movement, a central web portal was used as a common entry point for information on the movement. A host of mostly open-source, hosted tools were used in the portal to network, engage, and empower activists.

For example, Hackfoldr, an open-source multi-level bookmark framework that allows collaborative sharing of data, links, documents, and information from several sources, was used to organize links and allow everyone to keep up with daily changes. There were people and project registries – organized by tags, and real-time shared documents – using Hackpad and EtherCalc rather than wikis due to their ability to be shared in real time. Loomio allowed particular task forces to quickly make decisions. Having all this information in a central place also allowed for a translation team to quickly produce English language versions for international outreach.

Tech for Good Can Be a Public Good

“Taiwan is a very concrete example of why is it so important to use software that is serving people, and providing community structure for a public good,” said Knight.

Key Takeaways

Work with the tech community from the start. The Sunflower movement tapped into an existing community of open source and technology activists in Taiwan, who then played a key role in setting up the tools and platforms that enabled mass mobilization.

Facebook and Twitter can be limiting. Organizers purposely choose to avoid using big social media platforms for coordination due to their closed environment, limited adaptability, lack of collaborative functionality, and security concerns.

Issues over labels. Many of those who participated in the Taiwan protests did not do so on behalf of a political party or large NGO, and attempts by such organizations to co-opt the movement mostly failed. The issue of free trade and sovereignty was central and provided a powerful rallying point.

Scale decisionmaking. Numerous organizations participated in the Sunflower Movement but no single person (or group) dominated decision-making.

Open Source = Rapid Adaptability. When organizers decided to adopt Loomio, the fact that it was open source allowed them to translate the entire platform to Chinese in a single day, something that would have been impossible with a proprietary system. That also means that people all across Taiwan can now use Loomio in numerous different contexts, providing this potentially empowering tool to everyone.

“The stakes are not higher in any [other] digitized nation,” said Colin Megill, a founder of Pol.is, a non-hierarchical commenting platform that has also seen early adoption in Taiwan. “Who speaks for the Taiwanese people is always contested.”

Many observers noted that the Sunflower Movement was incredibly disciplined, peaceful, and focused, and though there were leaders, the groundswell had a strong sense of collaborative, decentralized authority.

“It really felt like an evolution in social movement discourse,” said Knight. “They were really explicit about need for horizontal organization structure, and a really high level of coordination. Having both of those things in the discourse and in the intention of the movement made it much more powerful.”

The Long Tail of Distributed Organising

The movement was ultimately successful in its goal – allowing for more public engagement on the trade deal – but also in its broader goal of transforming Taiwanese democracy. For example, following the movement, Loomio was used by the Taiwanese Ministry of Economic Affairs to host a public engagement – exactly what that Loomio hopes to see replicated by governments across the world. In addition, the country saw Pol.is used to solicit community input on municipal regulation of Uber. More recently, a conference, the g0v summit, brought digital democracy activists and technologists to collaborate on future open source, participatory tools.

“The political landscape has changed after [the Sunflower Movement]. People began to demand that political decisions are the result of a deliberative democracy, not just elected officials,” said Tang.

Renee Chou of Greenpeace Taiwan elaborated on the long-term changes of the movement and technology. “One of the best things that come out of that movement is how governments became, or was forced to become, more transparent,” Chou said. She noted that a website called musou (國會無雙) was set up to stream sessions in the legislative yuan and described that transparency as influencing how Dr. Ko Wen-je, a 2014 candidate for mayor of Taipei, ran his campaign. Further inspired by g0v, Ko disclosed all campaign expenditures on a google spreadsheet and, after being elected, disclosed Taipei’s 2016 budget online.

Knight points to the deliberate decentralized decisionmaking and focus on bottom-up engagement as keys to the success of both the Sunflower Movement, but also future mass mobilizations around the world.

“The [Sunflower movement] really reinforced to me that this wave of well-coordinated, citizen-driven, self-organizing social movements is still continuing and becoming more intentional and aware about organizational dynamics, about coordination, about mass collaboration and the things that it can enable,” said Knight.

Top photo by tenz1225 (Flickr: 2014.3.30 黑潮反服貿) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons